The Penitential Psalms in the Liturgy of Lent

In his Life of St Augustine, St Possidius of Calama writes that in his final illness, the great doctor “had ordered the Psalms of David, those very few which concern penance, be written out; and lying on his bed … read the four of them (from the pages) attached to the wall, and wept copiously and continuously.” (chapter 31) He does not say which four these were, but we may safely assume that Psalm 50, often known by its first word in Latin, “Miserere”, was included among them, long recognized as the penitential psalm par excellence. The Funeral of St Augustine, by Benozzo Gozzoli, 1465, in the church of St Augustine in San Geminiano, Italy.In the following century, Cassiodorus (ca 485-585), in his massive Exposition of the Psalms, refers in many places to the Penitential Psalms as a group, and when commenting on the first of them, Psalm 6, lists the others, according to the traditional numbering of the Septuagint: 31, 37, 50, 101, 129 and 142. (The list is given twice more, in the comments on Psalms 50 and 142.) At the conclusion of this section, he states that these seven are especially worthy of attention, since they “are given to the human race as an appropriate medicine, from which we receive a most salutary cleansing of our souls, revive from our sins, and by mourning, come to eternal joy.” As he explains each one individually, he often relates it in some way to one or more of the other six, as for example Psalm 142, which is placed last in the group “because these psalms begin from afflictions, and end in joys, lest anyone despair of that forgiveness which he knows has been set forth in these prayers.”Cassiodorus takes it for granted that his reader know this tradition, and therefore we may safely assume it was already part of the Church’s prayer by his time; his influence was very strong in the Middle Ages, and we may also assume that his writing did much to solidify its place in the liturgy. They were added to a variety of rites, such as the dedication of a Church according to the Roman Pontifical; in the traditional ordination rite, the bishop enjoins those who receive tonsure and the minor orders “to say one time the seven Penitential Psalms, with the Litany (of the Saints) and the versicles and prayers (that follow).”

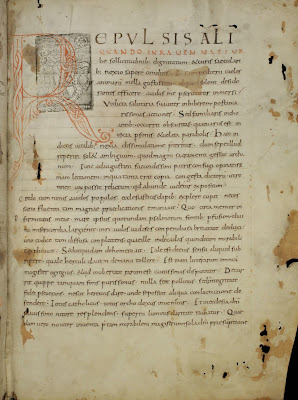

The Funeral of St Augustine, by Benozzo Gozzoli, 1465, in the church of St Augustine in San Geminiano, Italy.In the following century, Cassiodorus (ca 485-585), in his massive Exposition of the Psalms, refers in many places to the Penitential Psalms as a group, and when commenting on the first of them, Psalm 6, lists the others, according to the traditional numbering of the Septuagint: 31, 37, 50, 101, 129 and 142. (The list is given twice more, in the comments on Psalms 50 and 142.) At the conclusion of this section, he states that these seven are especially worthy of attention, since they “are given to the human race as an appropriate medicine, from which we receive a most salutary cleansing of our souls, revive from our sins, and by mourning, come to eternal joy.” As he explains each one individually, he often relates it in some way to one or more of the other six, as for example Psalm 142, which is placed last in the group “because these psalms begin from afflictions, and end in joys, lest anyone despair of that forgiveness which he knows has been set forth in these prayers.”Cassiodorus takes it for granted that his reader know this tradition, and therefore we may safely assume it was already part of the Church’s prayer by his time; his influence was very strong in the Middle Ages, and we may also assume that his writing did much to solidify its place in the liturgy. They were added to a variety of rites, such as the dedication of a Church according to the Roman Pontifical; in the traditional ordination rite, the bishop enjoins those who receive tonsure and the minor orders “to say one time the seven Penitential Psalms, with the Litany (of the Saints) and the versicles and prayers (that follow).” One of the oldest manuscripts of Cassiodorus’ Exposition of the Psalms, from the library of the Swiss monastery of San Gallen. (Cod. Sang. 200, 950-75 A.D.)Of course, they are particularly prominent in the liturgy of Lent. The customary of the Papal court known as the Ordinal of Innocent III (1198-1216) prescribes that they be said after Lauds every ferial day of Lent, together with the Litany of the Saints. To these were added the fifteen Gradual Psalms (119-133) before Matins, and the Office of the Dead, a burden which unquestionably increased the temptation to add more Saints to the calendar, since these supplementary Offices were routinely omitted on feast days. The Breviary of St Pius distributed them over the days of the week, so that the Office of the Dead would be said on the first ferial day of each week of Lent, the Gradual Psalms on Wednesdays and the Penitentials on Fridays, if the Office was of the feria. This remained in force until the reform of St Pius X, in which all mandatory recitation of them in the Office was abolished; the Gradual and Penitential Psalms are not included as specific groups in the post-Conciliar Liturgy of the Hours.The Use of Rome, with characteristic simplicity, simply recites the Psalms as a group with a single antiphon, based on the words of Tobias 3, 3-4: “Ne reminiscaris Domine delicta nostra, vel parentum nostrorum: neque vindictam sumas de peccatis nostris. – Remember not, Lord, our offenses, nor those of our forefathers, nor take Thou vengeance upon our sins.” In other Uses, the antiphon was followed by a series of versicles like those sung with the Litany of the Saints, and various prayers; this custom was highly developed in German-speaking lands, less so elsewhere. At Augsburg, for example, each day of the week had a different collect to conclude the recitation of the Penitential Psalms; the prayer for Monday was as follows.“Deus, qui confitentium tibi corda purificas, et accusantes se ab omni vinculo iniquitatis absolvis: da indulgentiam reis, et medicinam tribue vulneratis; ut percepta remissione omnium peccatorum, in sacramentis tuis sincera deinceps devotione permaneamus, et nullum redemptionis æternæ sustineamus detrimentum.O God, who purify the hearts of those that confess to Thee, and release from every bond those that accuse themselves, grant forgiveness to the guilty, and bring healing to the wounded, so that, having received the remission of all sins, we may henceforth abide in Thy sacraments with true devotion, and suffer no detriment to eternal salvation.”

One of the oldest manuscripts of Cassiodorus’ Exposition of the Psalms, from the library of the Swiss monastery of San Gallen. (Cod. Sang. 200, 950-75 A.D.)Of course, they are particularly prominent in the liturgy of Lent. The customary of the Papal court known as the Ordinal of Innocent III (1198-1216) prescribes that they be said after Lauds every ferial day of Lent, together with the Litany of the Saints. To these were added the fifteen Gradual Psalms (119-133) before Matins, and the Office of the Dead, a burden which unquestionably increased the temptation to add more Saints to the calendar, since these supplementary Offices were routinely omitted on feast days. The Breviary of St Pius distributed them over the days of the week, so that the Office of the Dead would be said on the first ferial day of each week of Lent, the Gradual Psalms on Wednesdays and the Penitentials on Fridays, if the Office was of the feria. This remained in force until the reform of St Pius X, in which all mandatory recitation of them in the Office was abolished; the Gradual and Penitential Psalms are not included as specific groups in the post-Conciliar Liturgy of the Hours.The Use of Rome, with characteristic simplicity, simply recites the Psalms as a group with a single antiphon, based on the words of Tobias 3, 3-4: “Ne reminiscaris Domine delicta nostra, vel parentum nostrorum: neque vindictam sumas de peccatis nostris. – Remember not, Lord, our offenses, nor those of our forefathers, nor take Thou vengeance upon our sins.” In other Uses, the antiphon was followed by a series of versicles like those sung with the Litany of the Saints, and various prayers; this custom was highly developed in German-speaking lands, less so elsewhere. At Augsburg, for example, each day of the week had a different collect to conclude the recitation of the Penitential Psalms; the prayer for Monday was as follows.“Deus, qui confitentium tibi corda purificas, et accusantes se ab omni vinculo iniquitatis absolvis: da indulgentiam reis, et medicinam tribue vulneratis; ut percepta remissione omnium peccatorum, in sacramentis tuis sincera deinceps devotione permaneamus, et nullum redemptionis æternæ sustineamus detrimentum.O God, who purify the hearts of those that confess to Thee, and release from every bond those that accuse themselves, grant forgiveness to the guilty, and bring healing to the wounded, so that, having received the remission of all sins, we may henceforth abide in Thy sacraments with true devotion, and suffer no detriment to eternal salvation.” The beginning of the Penitential Psalms in the Book of Hours of Louis de Roncherolles, end of the 5th or beginning of the 16th century. (Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Ms-1191 réserve, Bibliothèque nationale de France)At Salzburg, the intentions for reciting the Penitential Psalms were summed up in the following prayer, attested in a few other breviaries and books of hours.“Suscipere digneris, omnipotens Deus, hos septem psalmos consecratos, quos ego indignus et peccator decantavi in honore nominis tui, et beatissimæ Genitricis tuæ Virginis Mariæ, in honore sanctorum Angelorum, Prophetarum, Patriarcharum, in honore sanctorum Apostolorum, in honore sanctorum Martyrum, Confessorum, Virginum et Viduarum, et sanctorum Innocentum, in honore omnium Sanctorum, pro me misero famulo tuo N., pro cunctis consanguineis meis, pro omnibus amicis et inimicis meis, pro omnibus his qui mihi bona et mala fecerunt, vivis et defunctis: concede, Domine Jesu Christe, ut hi psalmi proficiant nobis ad salutem et veram pænitentiam agendam, et vitam æternam consequendam.Deign thou to receive, almighty God, these seven holy psalms, which I, though unworthy and a sinner, have sung unto the honor of Thy name, and of Thy most blessed Mother the Virgin Mary, to the honor of the holy Angels, Prophets and Patriarchs, to the honor of the holy Apostles, to the honor of the holy Martyrs, Confessors, Virgins and Widows, and the Holy Innocents, to the honor of all the Saints, for myself Thy wretched servant, for all my relatives, for all my friends and enemies, for all those who have done me good and ill, both living and dead; grant, o Lord Jesus Christ, that these Psalms may profit us unto salvation and the doing of true penance, the obtaining of eternal life.”The Penitential Psalms were also generally used at the beginning of Lent, at the ceremony by which the public penitents were symbolically expelled from the church, and again on Holy Thursday, when they were brought back in. These ceremonies were particularly elaborate in the Use of Sarum, but similar rites were observed in a great many other places. After Sext of Ash Wednesday, a sermon was given; a priest in red cope, accompanied by deacon, subdeacon and the usual minor ministers, then prostrated before the altar, while the choir said the seven penitential psalms. At the end of these were said a series of versicles and prayers, most of which refer directly to the public penitents.“Dómine Deus noster, qui offensióne nostra non vínceris, sed satisfactione placaris: réspice, quæsumus, super hos fámulos tuos, qui se tibi gráviter peccasse confitémur: tuum est enim absolutiónem críminum dare, et veniam præstáre peccántibus, qui dixisti pænitentiam te malle peccatóris quam mortem. Concéde ergo, Dómine, his fámulis tuis, ut tibi pænitentiæ excubias celebrant; et correctis áctibus suis, conferri sibi a te sempiterna gaudia gratulentur.Lord our God, who are not overcome by our offense, but appeased by satisfaction; look we beseech Thee, upon these Thy servants, who confess that they have gravely sinned against Thee; for it is Thine to give absolution of crimes, and grant forgiveness to those who sin, even Thou who said that Thou wishest the repentance of sinners, rather than their death. Grant therefore, o Lord, to these Thy servants, that they may keep the watches of penance, and by correcting their deeds, rejoice that eternal joys are given them of Thee.”The ashes were then blessed, followed by a procession, which, as I noted in an article last week, was a normal part of the Ash Wednesday ceremonies in the Middle Ages. The Sarum Processional specifies that a cross was not used, but an “ash-colored banner” was carried instead at the head of the procession. At the door, the penitents were taken by the hand, and led out of the church, while the following responsory was sung, reprising an ancient theme of meditation on the Fall of Man in the readings of Genesis in Septuagesima.

The beginning of the Penitential Psalms in the Book of Hours of Louis de Roncherolles, end of the 5th or beginning of the 16th century. (Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Ms-1191 réserve, Bibliothèque nationale de France)At Salzburg, the intentions for reciting the Penitential Psalms were summed up in the following prayer, attested in a few other breviaries and books of hours.“Suscipere digneris, omnipotens Deus, hos septem psalmos consecratos, quos ego indignus et peccator decantavi in honore nominis tui, et beatissimæ Genitricis tuæ Virginis Mariæ, in honore sanctorum Angelorum, Prophetarum, Patriarcharum, in honore sanctorum Apostolorum, in honore sanctorum Martyrum, Confessorum, Virginum et Viduarum, et sanctorum Innocentum, in honore omnium Sanctorum, pro me misero famulo tuo N., pro cunctis consanguineis meis, pro omnibus amicis et inimicis meis, pro omnibus his qui mihi bona et mala fecerunt, vivis et defunctis: concede, Domine Jesu Christe, ut hi psalmi proficiant nobis ad salutem et veram pænitentiam agendam, et vitam æternam consequendam.Deign thou to receive, almighty God, these seven holy psalms, which I, though unworthy and a sinner, have sung unto the honor of Thy name, and of Thy most blessed Mother the Virgin Mary, to the honor of the holy Angels, Prophets and Patriarchs, to the honor of the holy Apostles, to the honor of the holy Martyrs, Confessors, Virgins and Widows, and the Holy Innocents, to the honor of all the Saints, for myself Thy wretched servant, for all my relatives, for all my friends and enemies, for all those who have done me good and ill, both living and dead; grant, o Lord Jesus Christ, that these Psalms may profit us unto salvation and the doing of true penance, the obtaining of eternal life.”The Penitential Psalms were also generally used at the beginning of Lent, at the ceremony by which the public penitents were symbolically expelled from the church, and again on Holy Thursday, when they were brought back in. These ceremonies were particularly elaborate in the Use of Sarum, but similar rites were observed in a great many other places. After Sext of Ash Wednesday, a sermon was given; a priest in red cope, accompanied by deacon, subdeacon and the usual minor ministers, then prostrated before the altar, while the choir said the seven penitential psalms. At the end of these were said a series of versicles and prayers, most of which refer directly to the public penitents.“Dómine Deus noster, qui offensióne nostra non vínceris, sed satisfactione placaris: réspice, quæsumus, super hos fámulos tuos, qui se tibi gráviter peccasse confitémur: tuum est enim absolutiónem críminum dare, et veniam præstáre peccántibus, qui dixisti pænitentiam te malle peccatóris quam mortem. Concéde ergo, Dómine, his fámulis tuis, ut tibi pænitentiæ excubias celebrant; et correctis áctibus suis, conferri sibi a te sempiterna gaudia gratulentur.Lord our God, who are not overcome by our offense, but appeased by satisfaction; look we beseech Thee, upon these Thy servants, who confess that they have gravely sinned against Thee; for it is Thine to give absolution of crimes, and grant forgiveness to those who sin, even Thou who said that Thou wishest the repentance of sinners, rather than their death. Grant therefore, o Lord, to these Thy servants, that they may keep the watches of penance, and by correcting their deeds, rejoice that eternal joys are given them of Thee.”The ashes were then blessed, followed by a procession, which, as I noted in an article last week, was a normal part of the Ash Wednesday ceremonies in the Middle Ages. The Sarum Processional specifies that a cross was not used, but an “ash-colored banner” was carried instead at the head of the procession. At the door, the penitents were taken by the hand, and led out of the church, while the following responsory was sung, reprising an ancient theme of meditation on the Fall of Man in the readings of Genesis in Septuagesima. An illustration from a Sarum Processional of the Ash Wednesday procession; the captions reads “The station on the day of ashes, when the bishop expels the penitents.” The ash-colored banner is seen up top. Reproduced in a modern edition by WG Henderson, 1882. (This would seem to be one of the inspirations for Fr Fortescue’s famous little illustrations in the Ceremonies of the Roman Rite.)R. Behold, Adam is become like one of us, knowing good and evil; see ye lest he take of the tree of life, and live forever. V. The Cherubim, and the flaming, turning sword, to guard the way to the tree of life. See ye…On Holy Thursday, when the penitents were brought back into the church, usually referred to as their “reconciliation”, the process was reversed, again by a priest in a red cope, accompanied by the various grades of ministers and the ash-colored banner. This ceremony deserves its own post, which I shall do on Holy Thursday; suffice it therefore to note here that the penitential Psalms are said again before the final absolution is imparted.

An illustration from a Sarum Processional of the Ash Wednesday procession; the captions reads “The station on the day of ashes, when the bishop expels the penitents.” The ash-colored banner is seen up top. Reproduced in a modern edition by WG Henderson, 1882. (This would seem to be one of the inspirations for Fr Fortescue’s famous little illustrations in the Ceremonies of the Roman Rite.)R. Behold, Adam is become like one of us, knowing good and evil; see ye lest he take of the tree of life, and live forever. V. The Cherubim, and the flaming, turning sword, to guard the way to the tree of life. See ye…On Holy Thursday, when the penitents were brought back into the church, usually referred to as their “reconciliation”, the process was reversed, again by a priest in a red cope, accompanied by the various grades of ministers and the ash-colored banner. This ceremony deserves its own post, which I shall do on Holy Thursday; suffice it therefore to note here that the penitential Psalms are said again before the final absolution is imparted.