A New Monastery in the Midwest

My contributions here been a bit scarce of late but our readers will be pleased to hear that I have a very good reason for my silence. Some time ago, I accepted a position at Cram and Ferguson Architects in Concord, Massachusetts. We have had, in this difficult economic time, the blessing of being quite busy. One of the most exciting new projects to come into the firm during this time is a new design for a monastery in Wisconsin. It will be the new home of the nuns of Valley of Our Lady Monastery. It has been a great pleasure to be a member of the design team working on this project.

My contributions here been a bit scarce of late but our readers will be pleased to hear that I have a very good reason for my silence. Some time ago, I accepted a position at Cram and Ferguson Architects in Concord, Massachusetts. We have had, in this difficult economic time, the blessing of being quite busy. One of the most exciting new projects to come into the firm during this time is a new design for a monastery in Wisconsin. It will be the new home of the nuns of Valley of Our Lady Monastery. It has been a great pleasure to be a member of the design team working on this project.

Valley of Our Lady has attracted a significant number of new vocations in the past decade. Its Cistercian sisters wear the habit, pray the Liturgy of the Hours with great devotion, and live a simple, cloistered life in common. They maintain themselves through the making of altar breads and other craft products. Firm principal Ethan Anthony, who has undertaken multiple visits to the historic “Three Sisters of Provence”— the ancient Cistercian monasteries of Le Thoronet, Sénanque, and Silvacane—has worked closely with the sisters to ensure the new monastery fulfils both their spiritual and practical needs. One of the largest projects undertaken by the firm in recent years, it is, to my knowledge, the first new traditional ecclesiastical project to draw on the simplicity and balance of Cistercian monastic architecture, and the first ever undertaken in the United States.

The roots of Cistercian architecture lie in the order’s first great expansion under St. Bernard of Clairvaux in the second quarter of the twelfth century. Seeking to avoid Cluniac bombast, the order set forth clear and concise recommendations for the layout and design of Citeaux’s numerous daughter houses. While St. Bernard must be considered the father, or at least godfather, of Cistercian architecture, it is the time-tested product of the accumulated historical experience of the order. Cistercian architecture has eschewed superfluous decoration in favor of a beauty built on harmonious shapes, enduring materials, and a web of interrelated proportions. Symbolic ornament is always sparing and, when added, its content and placement is carefully attuned to the order’s liturgical spirituality. The standardized building layout was conditioned by a desire to balance the order’s contemplative mission with its robust tradition of work-as-prayer. Cistercian monasteries in Europe have included, alongside church and refectory, forges, water-mills and barns of surprising beauty. In drawing on these models, Cram and Ferguson Architects does not merely seek to imitate the medieval past. Instead, we have sought to create a sense of organic continuity with St. Bernard’s vision, adapted to the requirements of modern construction and budget, as well as the demanding climate of the region. The structure is not a copy, but a literate and thoughtful projection of the Cistercian ideal forward into the present and future.

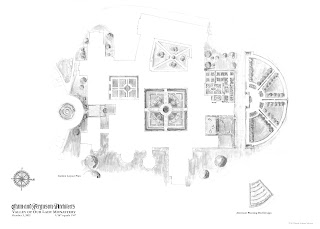

The monastery, which will house 35 sisters, is dramatically placed atop a hill, but is sufficiently screened from nearby roads to ensure privacy. It is arranged around three courtyards; the principal cloister is centered on a fountain whose shape is inspired by the St. Benedict medal, while the other two form spaces are linked programmatically to the monastery bakery and the church. A guest-house for family and aspirants forms two sides of the church cloister. The library, refectory and infirmary lie off the main cloister, the latter two with superb views of the rolling countryside. An octagonal chapter-house is located near the north transept of the church. The church, which includes both screened choir seating for the nuns and a small section for lay visitors, was the result of months of detailed study by the firm. Ethan Anthony was particularly concerned to ensure that the interior should be designed to ensure the best natural lighting, like its European cousins, a challenge with Wisconsin’s high latitude and long winter nights. The architecture of the interior is simple but beautifully-proportioned, and the entire building, save the vaults, will be faced with stone. A two-stage lantern will house bells and admit daylight into a domical crossing-vault. A small closed gallery in the transept will allow the infirm to participate in the liturgical Hours.

The remainder of the complex, while simpler in its vocabulary and detailing, is nonetheless governed by the same rules and harmonious design. Water will run throughout the entire complex in the forms of fountains and interlinked channels, giving a welcome note of movement and sound to its gardens. The second storey includes a patio above the main courtyard and a smaller upper cloister ringed with the nuns’ simple cells. The bakery, located to the west of the complex, is the most utilitarian of the complex’s structures, but features a large, top-lit production area intended to provide a simple but pleasing workspace for the sisters, who will spend much of their day-to-day life within its walls.

As can be seen from these images, the design is far advanced, but still under continual refinement and development. More images can be see at Cram and Ferguson Architects' website. Regular updates about the monastery project, as well as information for potential aspirants and donors, can be found at this website: http://www.valleyofourlady.org/. Other information about the monastery can be found at: http://nunocist.org/. On completion, the new Valley of Our Lady will be a fitting addition to the long tradition of Cistercian simplicity and a worthy place for prayer, contemplation, and Godly work.